I have just published a science fiction novel, Traveling in Space,

and there is a bit of an irony in that. When I was in high school and college I was lucky to achieve even a D in science courses, and to this day any math beyond the four basics — addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division — puts me into a cold sweat. Even the four basics would bother me if some kind strangers had not invented the hand held electronic calculator.

Granted there is no hard science in my novel and the only math is the word count, but still — a science fiction novel? I mean, any dummy can write a mystery, just create an amateur sleuth who has the same profession you have (so you can “write what you know”) and throw a dead body in their path. But science fiction? Shouldn’t the writer at least know how to do an equation?

Granted there is no hard science in my novel and the only math is the word count, but still — a science fiction novel? I mean, any dummy can write a mystery, just create an amateur sleuth who has the same profession you have (so you can “write what you know”) and throw a dead body in their path. But science fiction? Shouldn’t the writer at least know how to do an equation?

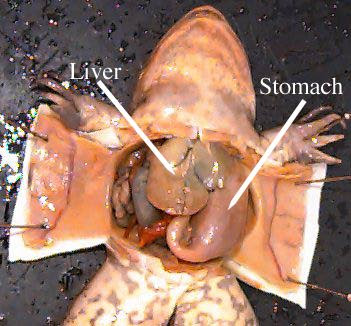

Not necessarily, I have to say in self-defense, because although science in my formative years would often make me sick to my stomach (and not just because I was dissecting a frog),

in my adult years the idea of science and its rational method, and the history of science and its incredible achievements in pushing upward the Homo sapiens species, have been the most delightful and important memes to meander joyfully in my mind. I date this conversion from watching Jacob Bronowski’s 1973 BBC series, The Ascent of Man (broadcast in America over PBS).

In this 13-part documentary series Dr. Bronowski presented his personal view of the flowering of human intelligence, especially through science, in an engaging and compelling manner that must have made his lectures in classrooms standing room only — as opposed to my science classes which were sleeping room only.

in my adult years the idea of science and its rational method, and the history of science and its incredible achievements in pushing upward the Homo sapiens species, have been the most delightful and important memes to meander joyfully in my mind. I date this conversion from watching Jacob Bronowski’s 1973 BBC series, The Ascent of Man (broadcast in America over PBS).

In this 13-part documentary series Dr. Bronowski presented his personal view of the flowering of human intelligence, especially through science, in an engaging and compelling manner that must have made his lectures in classrooms standing room only — as opposed to my science classes which were sleeping room only.

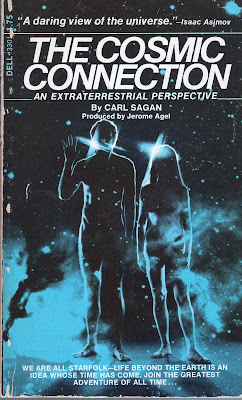

The Ascent of Man excited me about where humankind had come from and, more important, about where it might go. I began to understand the value of science and its method, not just in leading to technological toys we all enjoy and benefit from, but leading to an expansion of what we know and a maturation of our shared self. After Bronowski I discovered Carl Sagan, especially his early books such as The Cosmic Connection,

and went on from there to enjoy the great science writing we’ve had for the past forty years by such authors as Francis Crick, Paul Churchland, Robert Wright, Jonathan Weiner, Steven Pinker, Brian Green, Natalie Angier, Edward O. Wilson, Antonio Damasio, and, of course, Richard Dawkins, among others. Although the Ascent of Man and these books certainly include specific facts and data, what they really convey is the general personality of science, the overall thrust of what its method of inquiry can achieve, and the sense of wonder that the exploration and growing awareness of the universe around us — and within us — can engender.

and went on from there to enjoy the great science writing we’ve had for the past forty years by such authors as Francis Crick, Paul Churchland, Robert Wright, Jonathan Weiner, Steven Pinker, Brian Green, Natalie Angier, Edward O. Wilson, Antonio Damasio, and, of course, Richard Dawkins, among others. Although the Ascent of Man and these books certainly include specific facts and data, what they really convey is the general personality of science, the overall thrust of what its method of inquiry can achieve, and the sense of wonder that the exploration and growing awareness of the universe around us — and within us — can engender.

I’ve been thinking about all this recently while listening to conversations about public school education, especially two of the more interesting ones. One is cultural centering on the teaching of evolution and the proposed teaching of what I can only refer to as counter-evolution.

The other concerns the pragmatic push to turn around our country’s poor performance in high school science and math scores,

so we will have the required scientists, engineers, mathematicians, and technocrats to keep America competitive in the future. Certain participants in the first conversation seem to propose that we teach little or no science to anyone as it may offend someone; contributors to the second feel we should require more science for everyone in the hope that we can create many someones who will brilliantly make America economically strong again. Neither, it seems to me, is ideal. The first, not teaching science or teaching all theoretical comers — as if science was a democracy — is too absurd and silly a debate to need a comment from me. The second, required, intense, heavy on the details, math and science courses, sounds fine but I believe such requirements turn more students off than on, because, let’s face it, learning just the dry facts and details of science is hard going and many students, indeed most, might spend their time in class experiencing the same cold sweats I did, or, worse, a hateful indifference.

The other concerns the pragmatic push to turn around our country’s poor performance in high school science and math scores,

so we will have the required scientists, engineers, mathematicians, and technocrats to keep America competitive in the future. Certain participants in the first conversation seem to propose that we teach little or no science to anyone as it may offend someone; contributors to the second feel we should require more science for everyone in the hope that we can create many someones who will brilliantly make America economically strong again. Neither, it seems to me, is ideal. The first, not teaching science or teaching all theoretical comers — as if science was a democracy — is too absurd and silly a debate to need a comment from me. The second, required, intense, heavy on the details, math and science courses, sounds fine but I believe such requirements turn more students off than on, because, let’s face it, learning just the dry facts and details of science is hard going and many students, indeed most, might spend their time in class experiencing the same cold sweats I did, or, worse, a hateful indifference.

And yet, science education in this country needs improvement, not just so we can leap ahead of Europe and Asia in money making technology, but so we can have an informed population who, like it or not and for some time to come, will face ballot measures asking them to make general decisions on such subjects as abortion, stem cell research, sexual preferences and the rights desired or denied in such preferences, genetic modification, climate and energy issues, and other subjects that are best considered by an electorate with some science literacy. They will also be asked to elect candidates who will be tasked to make many specific decisions requiring more than a basic understanding of science. But how can the electorate judge a candidate’s level of understanding if they have little or none of their own?

I would like to propose an idea. This idea comes not only from my own history of cold sweats in science classes, but from the warm glow I felt in classes in the arts. First, we should stop requiring for high school graduation courses in several of the major sciences, rigorously testing students on their understanding of very specific details and minutia of biology, physics, geology, etc. These classes should be elective and only for those students who truly want to study a particular science. I suggest this, though, only if what is required for graduation are two other courses: Science Appreciation and the History of Science. These should be taken within the first two years of high school, and maybe previewed in middle school. For what is the use of leaning facts and data and details of individual sciences, and never learning what science, at its essence, truly is. Is it a philosophy, a modern religion, something only geeks care for, a mystic understanding of the fabric of the universe, or just a very boring set of dull and deadly facts?

Science should not be treated like a frog in formaldehyde — it should be understood and appreciated before you pull its guts out.

I have obviously taken this idea from long established art and music appreciation and history courses. Just as not everyone can draw or play music, not everyone is going to become a scientist, engineer or mathematician — no matter how badly the country might need them. And just as life is richer if you have an appreciation for art and music, our country and society would be richer if everyone had an appreciation of science — what it is and does and how it has spurred on, in Bronowski’s wonderful phrase, the Ascent of Man.

Science scares people. A knowledgeable understanding that science is simply a well-honed method of inquiry into, and discovery of, the laws of nature that discourages in its conclusions prejudices, biases, and subjectivity, and thus can better reveal, and revel in, the true awe and wonder of the universe, is the best way to alleviate the fear, far better than the thud-thud-thud of facts to be memorized. Good science appreciation and history courses taught by enthusiastic instructors will open and inform minds among the majority of students, and inspire some of those students — maybe more than one might think — to pursue with vigor careers in science and its related fields. Those are the students for the specific science classes of details and facts, and, well motivated, they will not sit in those classes suffering cold sweats.